Updated 8/14/2019

This tutorial

This tutorial aims to answer this question:

Now that I have a Linux system running, how do I go about learning more?

This tutorial is aimed at eager beginners and aspiring computer users that have decided to take control of their computing. It largely follows my journey to learn more about Linux specifically and computing more generally. My goal is that with this tutorial and a handful of things downloaded, you can sit with your computer—even without an Internet connection and learn more about computing.

My approach here is thematic; I go over some class of actions you might want to do, and then mention some options you may choose to succeed at doing these things.

Requirements

In this tutorial, I assume that you have a Linux system up and running (...and here, the term "Linux" is used to mean a UNIX or UNIX-like system that has certain core utilities, not the kernel itself or something highly technical like that). For something that just works, Manjaro and Xubuntu are some solid options. If you want to spend some more time configuring things, you may want to try installing Arch Linux. Really, it doesn't matter that much where you start because you are entering Linux land where customizability is king.

Editors

What is a samurai without a sword? You need an editor! Most things on

Linux are configurable via a "dot file", so called because they

have a name that starts with a dot (e.g. .bashrc,

.eslint...). You will need an editor to change these files. If you

are enthusiastic about learning Linux, you probably have some interest

in writing scripts or programs or some sort. You'll need an editor for

that too.

Learning the basics of some editor is a skill you will not

regret. Editors like vi and nano can be found pretty much

anywhere. It probably won't be too difficult for you to grab a more

sophisticated editor like vim, emacs, or Visual Studio Code.

The GUI way

There is a big movement to make Linux systems intuitive and "user-friendly", particularly for users coming from Windows and Mac. No explanations needed here—you can explore the menus and built in softwares with any Linux distribution that comes built in with a graphical desktop environment.

There is no shame in using and enjoying a GUI. For many things, this is the easiest way to get things done, particularly if you don't care to do any special configuration. Examples of things I've recently used GUI menus to configure:

- Themes/fonts

- Wallpaper

- Keyboard shortcuts

- Joining wifi networks

- Sound/volume stuff

Other tasks, such as managing software, is perhaps better done through the Command Line Interface (CLI).

Whispering into the soul of your system

Lots of things on modern computers are "artifacts of engineering", leftover remnants from designs of the past. One interesting example is the "command line interface" typically accessed through a terminal (emulator).

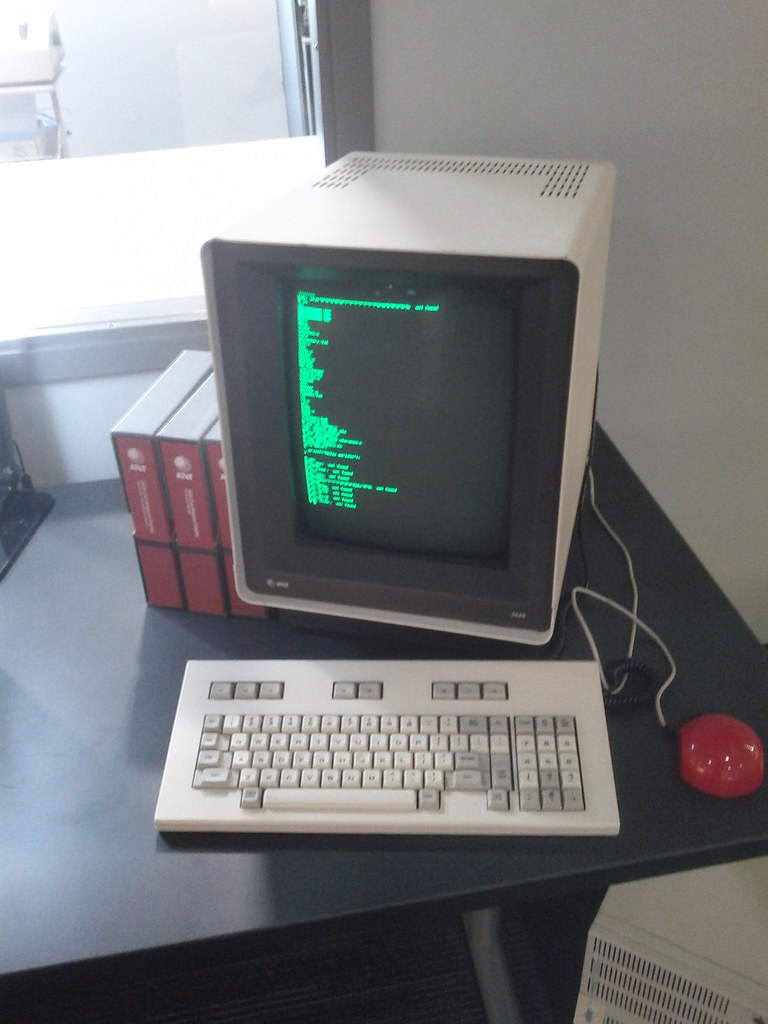

Computers used to look like this:

"IMG_20131027_152921"by S. F. is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In more current times, the old way of interacting with computers is emulated using what is usually called something like "terminal" or "shell" on modern systems.

Need moar software

Most Linux distributions ship with a package manager.

Exploring your filesystem

Typing stuff like ls -la all the time can get very tiring. One way

to get around this problem is to define aliases for commands you

commonly use.

Another way to get around your file sytem is to use a file manager

that runs on the command line (or within your favorite editor). For

example, there is vifm for doing common

operations like moving, copying, and renaming files in a vim editor

like way. Emacs has the built in

dired

mode to do these things.

Getting system info

To find out some quick information about your system and display it in

a pretty way, use your package manager to download and install

screenfetch. There are of course other places to find all of this

information, but this is the easiest way to getting system info (that

also looks cool) akin to doing the "about my computer" stuff on

Windows or MacOS.

Finding more information

Are there things that you don't understand? How do you find documentation for those things?

Clicking through menus

This is often how I learn more about the features of some program. You may discover useful commands you never thought you needed if you take the time to click through some menus.

I've found this especially helpful in using widely used, large, complex programs like GIMP (image manipulation) and Blender (3D graphics).

Built-in help systems

Many pieces of software come with their own built in help systems. Many (most?) users jump to searching the Internet for answers, but becoming familiar with the built-in help system for some software may be able to provide quicker, more specific answers if you invest a little bit of time to learn how to use it.

Documentation is often available for download for offline viewing. If you have a 12 hour flight coming up, why not read a user manual until you fall asleep? (either way, you win—you learn something or you get a good rest).

High quality online resources

Not all websites are created equal; finding the best websites can save you a lot of time you'd otherwise spend sifting through crap.

Rather than naïvely Googling how to do something on Linux, for instance, it may be helpful to first consult the Arch Wiki for Linux related topics. This resource can be useful even for non-Arch users that want to learn about some topic and Linux. For instance, recently I wanted to see what options were available for ripping CDs. The Arch Wiki had lots of helpful information for doing that on my (non-Arch) Debian-based system.